Program Booklet

Mahler's Symphony No. 1

Sunday

2:15 p.m.

to approximately 4:30 p.m.

A classic paired with rediscovered gems: the Residentie Orkest performs Mahler's Symphony No. 1, Titan, alongside works by the forgotten Jewish composer Schulhoff.

📳

Please put your phone on silent and dim the screen so as not to disturb others during the concert. Taking photos is allowed during applause.

Programme

Prior to this concert there will be a Starter at 1:30 pm. A lively and casual program with live performances by our own musicians and interviews with soloists and conductors. The Starter is free of charge and will take place in the Swing Foyer opposite the cloakroom.

Erwin Schulhoff ( 1894–1942)

Suite for Chamber Orchestra, Op. 37 ( 1921)

Ragtime

False Boston

Tango

Shimmy

Step

Jazz

Erwin Schulhoff ( 1894-1942)

Menschheit - Symphony for alto and orchestra, Op. 28 (1919)

The Bagpipes

Winged Lame Attempt

Often

Twilight

Insight

At intermission we will serve a free drink.

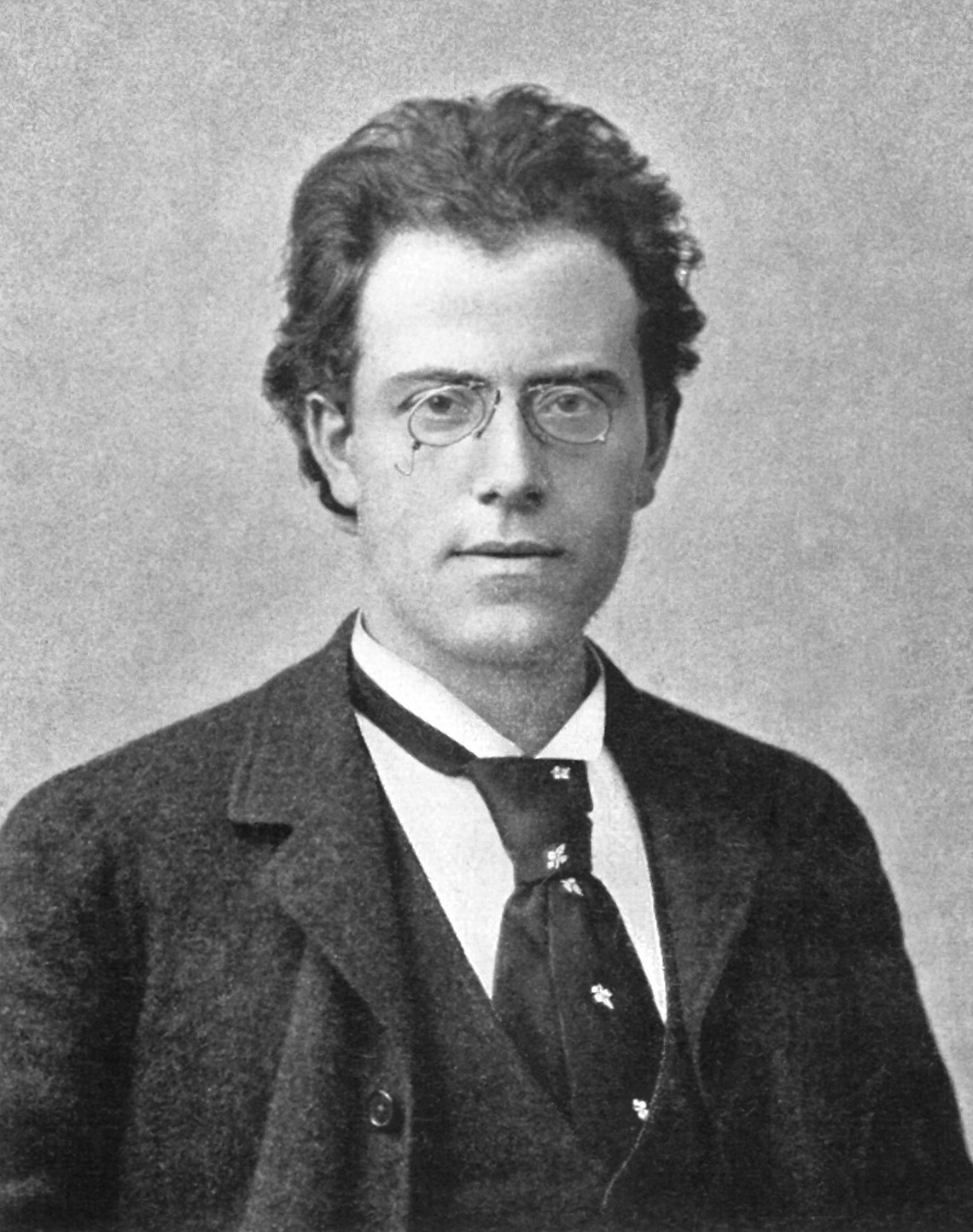

Gustav Mahler ( 1860-1911)

Symphony No. 1 in D major, "Titan" (1887-1888)

Slowly, sluggishly – Always very leisurely

Move vigorously, but not too quickly

Solemn and measured, without dragging

Stürmisch bewegt - Energetic

What are you going to listen to?

Both Schulhoff and Mahler were born in the Czech Republic. Both were also of Jewish descent. But while Mahler only occasionally encountered anti-Semitic elements in Vienna, where he lived and worked, Schulhoff paid for his Jewish roots and his sympathies for communism with his life under the Nazis.

War misery

It was Antonín Dvořák who helped his fellow countryman Erwin Schulhoff take his first steps on the musical path. He studied with Debussy and Reger, among others. A brilliant career lay ahead of him, until he was called up to serve in the Austrian army during the First World War. He witnessed indescribable misery, was wounded in the hand, and spent some time as a prisoner of war. After the war, he lived in Germany for several years, but found it difficult to let go of the horrors of war. Dancing was a way for him to calm his mind, and he visited numerous, sometimes obscure, dance venues. "I love dancing in nightclubs so much that I spent whole nights there dancing, with the pure happiness of the rhythm and my subconscious full of sensual pleasure," he wrote to Alban Berg. His Suite for Chamber Orchestra bears witness to this. It consists of six dances in which jazz plays an important role with ragtime and shimmy, but also Boston waltz and tango. Schulhoff does not simply imitate the dances. He takes their characteristic rhythms as a basis, but uses them to create his own music in a classical style. A beautiful mix of ballroom and Concert Hall.

Humanity

During these years, Schulhoff sought out extremes, flirting with anarchism and Dadaism. But could this help him process all his memories of his life as a soldier? Two years before his Suite , he composed Menschheit( ), a ‘Symphony for alto voice and orchestra’, as he himself called it. These are five songs based on texts by Theodor Däubler, in which Schulhoff clearly listened carefully to Mahler's orchestral songs. In the same way as his predecessor, he creates songs that easily rival Mahler's, with colorful orchestral sounds and an organic approach to vocal treatment. But Schulhoff, in keeping with Däubler's texts, is much more sombre than Mahler. No matter how lyrical the words may be, an undertone of sadness and unfulfilled longing lingers. This is most poignant in the Last . It is a warning to Mary that even her little Jesus cannot save her and that she must seek comfort in life herself.

From sunrise and funeral march to hell and heaven

It is almost impossible to determine exactly what Gustav Mahler meant with his Symphony No. 1. When he composed it around 1887-1888, he was already somewhat well-known as an opera conductor, but as a composer he still had a long way to go. At the premiere in Budapest in 1889, he presented it as a 'symphonic poem in two episodes', consisting of five separate movements, without further explanation. The music was unheard of and enigmatic to the audience and therefore received little acclaim. At a subsequent performance in Hamburg four years later, Mahler wrote an extensive program note in which he gave each movement a title and detailed commentary and gave the symphony the nickname 'Titan', after the book of the same name by Jean Paul. In later performances, however, Mahler radically removed all extra-musical references, including the title Titan, even removing one movement from and presenting it as a neutral four-movement symphony of purely absolute music.

Yet it is Mahler's detailed description that gives this symphony its deeper meaning. For then you experience how the work opens with a beautiful sunrise in spring, where we see a cheerful young man walking through the fields. He is a sturdy young man who dances in the prime of his life, as the second movement shows. The subsequent funeral march is ironic, even sarcastic. It is the animals of the forest who carry the hunter to his grave, complete with 'Father Jacob' in minor key and a mournful Bohemian folk song. And then the finale, 'dal inferno al paradiso' (from hell to heaven) in Mahler's experience. It begins as a hellish 'sudden outburst of despair, coming from a deeply wounded heart', as he himself described it, but gradually turns to luminous sounds, culminating in a heavenly chorale.

Kees Wisse

Prefer it on paper? Download a condensed printable version of this program.

Biographies

Residentie Orkest The Hague

Jun Märkl

Barbara Kozelj

Royal Conservatory

Would you like to read the lyrics of Schulhoff's "Menschheit"? Download them here!

Fun Fact

Clashing sounds

As in much of his music, Mahler often contrasts dramatic passages with folk-like melodies in his First Symphony . According to Freud, who treated the composer at the end of his life, this was related to an incident in his early childhood. One day, his parents had yet another violent argument. In a panic, the little boy ran outside, where he heard a barrel organ playing a cheerful folk tune in the village square. That striking contrast in atmosphere always stayed with him.

RO QUIZ

Has Mahler been to The Hague?-

Absolutely not

Good answer: yes you do

Mahler visited The Hague once. On October 2, 1909, he attended the performance of his Seventh Symphony in the no longer existing Building for Arts and Sciences. By automobile, a luxury at the time, Mahler entered The Hague with conductor Willem Mengelberg and friend and composer Alphons Diepenbrock. From hotel De Oude Doelen, where Mahler was staying, they took a ride to Scheveningen for a walk on the beach. However, this was not a great success. "The dreary loneliness of the sea disappearing in the fog and the colorless, closed hotels made Mahler nervous," an eyewitness recounted. They returned immediately.

-

Yes indeed

Good answer: yes you do

Mahler visited The Hague once. On October 2, 1909, he attended the performance of his Seventh Symphony in the no longer existing Building for Arts and Sciences. By automobile, a luxury at the time, Mahler entered The Hague with conductor Willem Mengelberg and friend and composer Alphons Diepenbrock. From hotel De Oude Doelen, where Mahler was staying, they took a ride to Scheveningen for a walk on the beach. However, this was not a great success. "The dreary loneliness of the sea disappearing in the fog and the colorless, closed hotels made Mahler nervous," an eyewitness recounted. They returned immediately.

-

Alone on the beach

Good answer: yes you do

Mahler visited The Hague once. On October 2, 1909, he attended the performance of his Seventh Symphony in the no longer existing Building for Arts and Sciences. By automobile, a luxury at the time, Mahler entered The Hague with conductor Willem Mengelberg and friend and composer Alphons Diepenbrock. From hotel De Oude Doelen, where Mahler was staying, they took a ride to Scheveningen for a walk on the beach. However, this was not a great success. "The dreary loneliness of the sea disappearing in the fog and the colorless, closed hotels made Mahler nervous," an eyewitness recounted. They returned immediately.

Good answer: yes you do

Mahler visited The Hague once. On October 2, 1909, he attended the performance of his Seventh Symphony in the no longer existing Building for Arts and Sciences. By automobile, a luxury at the time, Mahler entered The Hague with conductor Willem Mengelberg and friend and composer Alphons Diepenbrock. From hotel De Oude Doelen, where Mahler was staying, they took a ride to Scheveningen for a walk on the beach. However, this was not a great success. "The dreary loneliness of the sea disappearing in the fog and the colorless, closed hotels made Mahler nervous," an eyewitness recounted. They returned immediately.

Today in the orchestra

Help The Hague get music!

Support us and help reach and connect all residents of The Hague with our music.

View all program booklets

Be considerate of your neighbors and turn down your screen brightness.